Conservation vs. Development: The Hidden Costs of the Port of Barú in Panama

The Hidden Costs of the Port of Barú in Panama

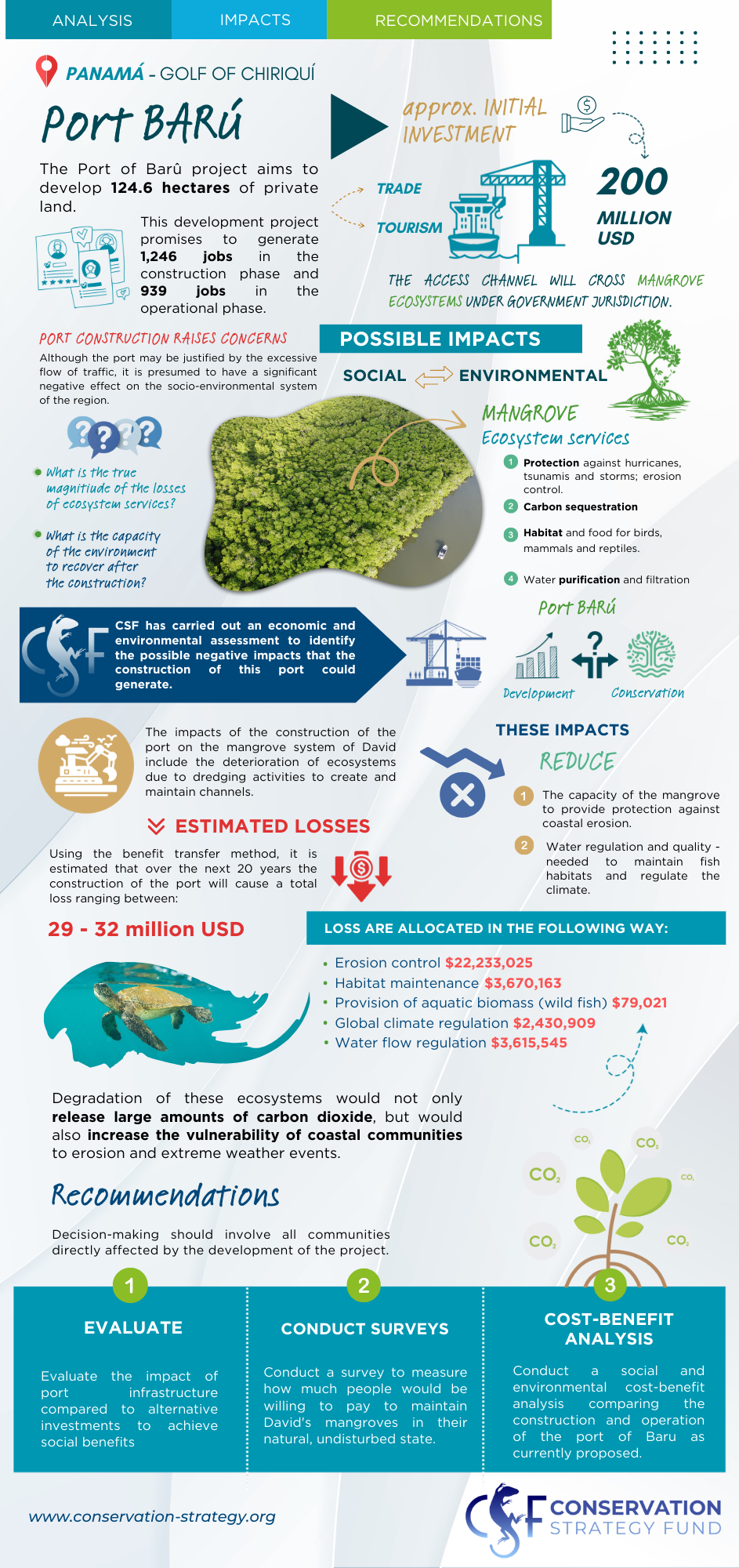

In the lush Chiriquí province of western Panama, a region known for its towering mountains, biodiverse rainforests, and rich coastal ecosystems, a proposed mega-development is stirring debate. The $200 million Port of Barú project promises economic growth and job creation—but it also threatens to unravel one of Panama’s most ecologically valuable coastal regions.

Conservation Strategy Fund (CSF) recently conducted a comprehensive analysis of the proposed port, evaluating its economic, social, and environmental impacts. The findings raise serious concerns about the project’s compatibility with Panama’s climate goals and long-term ecological health.

A Port with a Price

The Port of Barú, planned for the Gulf of Chiriquí, is envisioned as a hub for commercial cargo, tourism, and a duty-free zone. But to build it, developers would need to dredge nearly 20 miles of mangroves within the Manglares de David protected area—ecosystems that play a crucial role in carbon sequestration, biodiversity, and coastal protection: all essential elements of a strong economy. From construction to maintenance, the dredging and use of the port would be continuously destructive to the mangroves and the wildlife depending on them.

The Manglares de David ecosystem is home to a remarkable variety of wildlife, including bottlenose dolphins, humpback whales, and commercially important fish species. They are also the only site in Panama home to a significant population of the globally threatened Yellow-billed Cotinga (BirdLife). The destruction of these mangroves would disrupt fragile food webs, damage fisheries, and remove a critical natural buffer against storms and sea-level rise.

The Economic Case for Conservation

CSF’s ecosystem service valuation revealed that the environmental damage from port construction could cost between $29.6 million and $32 million over 20 years—and as much as $54.6 million when applying a more environmentally appropriate discount rate. The largest projected losses include:

- Soil erosion control: $22.2 million

- Habitat and nursery services: $3.7 million

- Water flow regulation: $3.6 million

- Global climate regulation: Up to $2.4 million

These are not abstract numbers—they reflect real, measurable losses in natural services that support livelihoods, especially for vulnerable communities like local fishermen who depend on healthy coastal ecosystems to replenish their fish stock.

CSF’s analysis also found that traditional Environmental Impact Assessments (EIAs) tend to underestimate these damages, failing to account for long-term and indirect impacts. As a result, decision-makers often lack the full picture when considering large-scale developments.

A Smarter Site?

Interestingly, the port doesn’t have to come at such a high environmental cost. A 2004 government-funded study identified Puerto Armuelles, also in the Barú District, as a promising alternative location. This site already benefits from government investment in infrastructure like roads and an airport, has calmer waters, and offers deeper natural harbors—making it both a practical and potentially less damaging option.

CSF integrated this information into its analysis, highlighting that sustainable alternatives are not only available—they are feasible and well-supported by past research.

The Missing Piece: Long-Term Impact

One of the most pressing challenges identified by CSF is the lack of long-term studies on the environmental and socioeconomic impacts of port construction. While ports are often promoted as engines of economic growth, there is limited research tracking how such projects affect ecosystems and communities over decades.

This information gap makes it harder to understand cumulative impacts on biodiversity, traditional livelihoods, and the long-term health of local economies. As Panama and other nations invest in infrastructure, filling this gap is essential to ensure development doesn’t come at the cost of environmental collapse.

Building a Better Future

The Port of Barú project highlights a broader truth: sustainable development requires a deeper integration of environmental and economic analysis. Without it, even well-intentioned infrastructure projects can cause irreversible harm.

CSF’s work empowers decision-makers and communities with the tools to evaluate trade-offs transparently and make choices that align with both national development goals and global climate commitments. As Panama moves forward, the hope is that projects like the Port of Barú will serve not just as blueprints for growth—but as opportunities to build a more resilient, sustainable future for all.

___

Watch this video to learn more about this study. (Vea este vídeo para obtener más información sobre este estudio.)

Read through this Infographic for more information about this project.

- Log in to post comments